Most tunes are built around a diatonic scale. The most well known diatonic scale is the major scale, C D E F G A B, but all seven cyclic permutations of those notes are named scales:

- C D E F G A B: major (I)

- D E F G A B C: dorian (II)

- E F G A B C D: phrigian (III)

- F G A B C D E: lydian (IV)

- G A B C D E F: mixolydian (V)

- A B C D E F G: minor (VI)

- B C D E F G A: locrian (VII)

Even though seven of these are possible, the only ones you generally run into in traditional music are major (I), minor (VI), mixolydian (V), and dorian (II).

Another way to think of these is as adding flats:

- no flats: C D E F G A B (I, major)

- add a flat seventh: C D E F G A Bb (V, mixolydian)

- add a flat third: C D Eb F G A Bb (II, dorian)

- add a flat sixth: C D Eb F G Ab Bb (VI, minor)

- add a flat second: C Db Eb F G Ab Bb (III, phrigian)

- add a flat fifth: C Db Eb F Gb Ab Bb (VII, locrian)

- flat first: Cb Db Eb F Gb Ab Bb (IV, lydian)

- flat fourth: Cb Db Eb Fb Gb Ab Bb (I, major)

This is correct, except that we switched down to Cb once it came time to flat the first.

The problem is that the major scale (I) isn't actually a great place to start: if we instead start with the lydian scale (IV) everything works:

C Db D Eb E F F# G Ab A Bb B IV 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 I 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 V 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 II 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 VI 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 III 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 VII 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

You can see that starting with the lydian scale each scale degree in turn is flattened: 4, 7, 3, 6, 2, 5. For more symmetry, each note to be flattened is a fifth down from the previous note to be flattened.

If we follow this pattern, flattening one note at a time, we can run through all the modes of all the keys:

A Bb B C Db D Eb E F F# G Ab A Bb B C IV 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 C I 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 C V 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 C II 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 C VI 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 C III 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 C VII 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 B IV 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 B I 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 B V 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 B II 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 B VI 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 B III 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 B VII 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bb IV 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bb I 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bb V 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bb II 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bb VI 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bb III 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bb VII 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 A IV 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 A I 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 A V 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 A II 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 A VI 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 A III 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 A VII 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

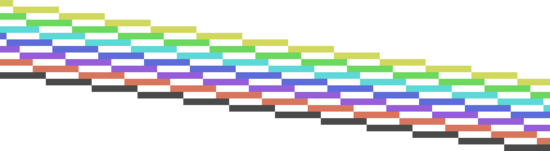

Turning this on it's side, it's really quite a pretty pattern:

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Stepping back, this makes it easy to think about what notes to expect in a mode:

- major: no extra flats

- mixolydian: one extra flat

- dorian: two extra flats

- minor: three extra flats

I find this framing much more useful than the cyclic permutation approach of thinking about starting the major scale on different notes.

(This also gets more elegant if we rename "F#" to "F" and "F" to "Fb". Then the lydian scale is C D E F G A B and all the other scales add flats from there.)

Comment via: google plus, facebook